As my turbulent flight to commercially spotlight African artists in the United States eases with time, modern-day African culture is finally becoming the hotbed for coverage on this side of the world. At every turn, there’s an Afro-this and an Afro-that, and Wizkid and Tems’ ‘Essence’ is killing the Billboard charts. However, Americans have yet to fully identify who the continent’s most valuable players are (See: Bia’s apology concerning Burna Boy, Wizkid, and Davido), so I hope to help demystify the unintentional mystery.

How do we do that as a community? To understand the weight and value of an international star is to first learn about them through authentic storytelling (viable media outlets, through pop culture leaders, and using social media as the best first-person perspective tool). Then, we need to share what we’ve learned with others online, and that’s how we do our part to create global sensations.

To my delight, last week, Nigeria’s larger-than-life musician Olamide came to New York City to promote his new album titled ‘UY Scuti’, which was inspired by his first son, who is just six years old.

Olamide recalled a conversation about astronomy with his six-year-old, “Hey, Dad, could you please tell me what the biggest star in the universe is?” Confessing that he also didn’t know the name of the smallest star in the universe, the YBNL Nation CEO said his son asked him to search for the answer on Google. When the ‘Rock’ singer found it on the search engine, he shared the result with his son.

“I just want you to know that I am smarter than you!” his boy exclaimed.

Naturally, I wanted to know if his biggest fan/son had a chance to listen to the album with the title he inspired. At the time of our interview, he hadn’t yet. Still, according to his father, he heard ‘Rock’, one of the best performing songs and videos from the album with over 4.2 million views and counting on its visual component; if you haven’t heard it yet, the hazy romantic Afrobeats track details what the Nigerian Hip-Hop legend wants to do with the special woman in his life and how he perceives her.

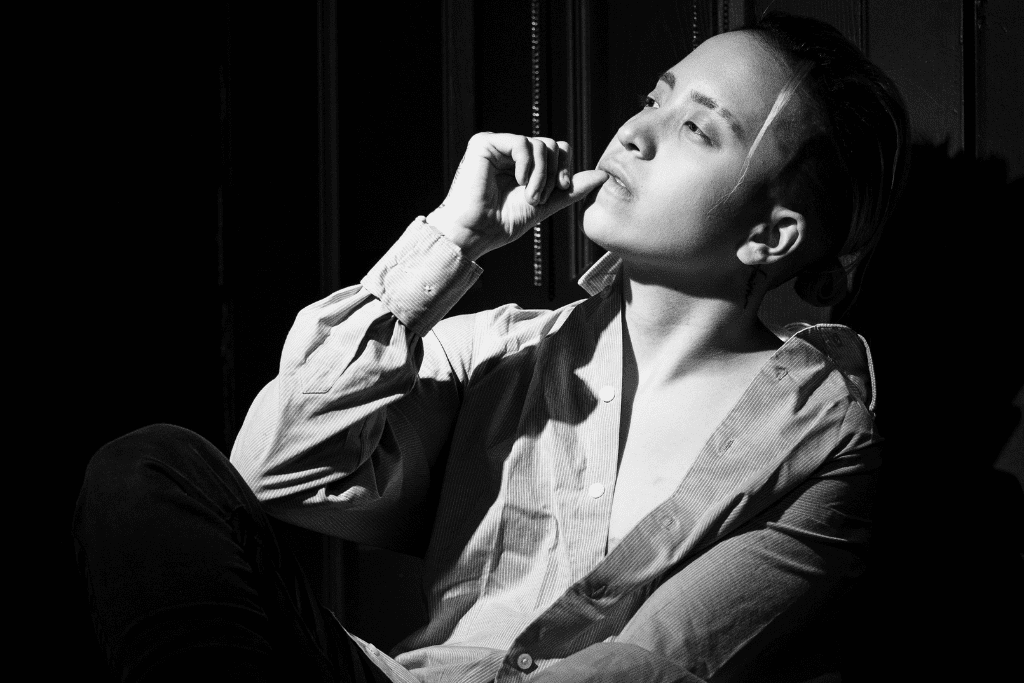

For it to be his first media run in this territory, fittingly, the big boys come out, including the Recording Academy/Grammy.com. With dark designer shades on, a mildly tattooed face, tightly-coiled hair, and a big Hennessy bottle sitting on the table, the Bariga, Lagos-born artist expressed that he has yet to breakthrough in the United States.

“If I am, to be honest, I can’t boldly tell you that I had [a] bro through here already”, Olamide laughed. “I feel like I’m just getting started cause most of the time when I come around to do shows out here, it’s mostly the African community and all that. So, until I start seeing other people that are not Africans, then, yeah. I’m just getting started.”

In Africa, mainly Nigeria and Ghana, before the global lockdown, other forms of West African music outside of Afrobeats and traditional styles of African music weren’t lucrative. Some West African rappers abandoned their local Hip-Hop sound or incorporated the commercial Afrobeats sound to be heard or taken seriously. (See Kofi Jamar, the very Olamide, and others).

As he took me down the path of his journey as one of the most successful rappers/artists on the continent, I wanted to know if he’s been affected by it and how he self-identifies in this space. Also, I could not help but ask about the current buzz term “Afrorap”, which officially debuted here on Grammy.com with the publication of fellow Nigerian recording artist Laycon’s performance for ‘All Over Me’.

The veteran rapper, songwriter, and label boss said the following when I asked if he was familiar with Afrorap, he replied:

Afrorap? Sorry, I didn’t know about that.

“It’s okay. I’m letting you know. It’s okay. Do you think that personifies your sound? And if not, how do you describe your music and your sound?”

“I mean, about two to three or four years ago, I would definitely fit in, but right now, I’m Afrobeats.”

We giggled together, and then I got back on track and said, “Based on my research, whenever I tried to look for specifically like Nigerian Drill music, or like Nigerian rap, as an outsider, it feels like people—moreso—they push Afrobeats…”

He interjected and said, “Most definitely. Sometimes, I don’t like to boxed, honestly speaking, but then again, we must find a way to put a face or some sort of identification to whatever it is we are doing. And if couple of people come together and say, “Okay, this is the way to identify this, and as long as the people that make those decisions are Africans, [it is okay].”

Olamide surprised me. He wasn’t loud, complicated, or uneasy; in fact, our traded humble demeanours made me more intrigued. I felt like I was talking to a friend, so I asked him more human-centric questions like his favourite album cut to perform (‘Julie’), the feeling for the album (“a companion project”), and if he dances (he doesn’t dance anymore due to his “bad ankles”).

In my own experience, I could only imagine how it felt to be an icon at home but considered a budding artist in a new land, so I asked him to tell me what it felt like for him to be in the States and if he values his current anonymity.

“It is a refreshing kind of like feeling. Though some people out here recognise my face, they’ve stumbled on my music, and all that, and my videos, but the approach is just way different than back home. It’s chill.”

I reassured him: “It’s going to catch up, though. I hope you’re ready. They’re going to be screaming your name.”

“I’m going to get some private island.”

“You might as well. You won’t be able to walk down the street when I’m done with you!”

We laughed.

Olamide’s presence crystallised a lot for me. It means Afrobeats is here. It’s only a matter of time.