Americans unified around the country to ensure young voters were active in the vital race to the polls this past Election season. Laurence Wilson is one of the young campaign workers who led the charge during President Joe Biden and United States Senator Raphael Warnock’s campaigns in Georgia. We continue to celebrate Black History Month with stories of past leaders, as well as, the stories our future leaders are currently creating. Laurence Wilson earned the nickname, “Baby Obama,” inspired by our former President Barack Obama, because of his innate sense of leadership and commitment to his community. We had the opportunity to discover more about Wilson’s dedication to politics, rallying his community and the entertainment industry, and the process of running a successful campaign.

Read our conversation with this impressive young political leader, Laurence Wilson, below:

How were you introduced to politics?

I was born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri, and I got my start in politics when I was thirteen. My mentor William Lacy Clay was in Congress for twenty years [and his father William Lacy Clay Sr. also served in Congress for more than three decades). He’s also my cousin. (Laughs) So I was a little kid knocking on doors when he was running [for office]. He had been in the state legislature in Missouri for seventeen years before he ran for Congress in 2000. So I was a little kid knocking on doors, making phone calls, not really knowing what I was doing, but I just kinda caught the [politics] bug and rode that wave.

In high school, I interned with him through the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation. I graduated from high school in 2006 and [enrolled at an HBCU,] the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. Initially, I was planning to become a film director. The summer after my freshman year of college [Congressman Clay] asked me to come and be a Congressional Black Caucus intern, so I spent the summer of 2007 working on Capitol Hill. [It was interesting] seeing the day-to-day workings of Congress and how all of that works.

[Congressman Clay] took me to a private meeting with then-Senator Obama, who was running for president at the time, and members of the Congressional Black Caucus who had endorsed him. I sat behind him for an hour and a half and was amazed by [the thought that] ‘Wow, this could be the first black president. This is historic.’ I was the only one among my peers who got that opportunity, and it was just an amazing experience.

[After meeting Obama] I got really involved in the political process. I went back to my university and changed my major to Political Science. I was deemed the ‘baby Obama.’ I helped get my whole campus registered to vote, just giving [my peers] an inside [look] at how a political campaign operates, helping to get people motivated and excited. I also interned with the Department of Homeland Security, and, because I have a minor in International Relations, I studied abroad in China. I wanted to see the world away from the United States, so I spent two months in China to get first-hand real-world experience.

How did you get students involved on campus?

Outside of just registering people to vote, I’d talk about the electoral college. I’d explain why it was important to bring your neighbors to the table, why it’s important to have conversations and knock on doors. [Grassroots] organizing is really just talking to your peers and finding common ground.

As an organizer, one of the things I talked about often was [the struggle to pass] the Affordable Care Act. I lost my healthcare coverage when I turned 23, before the law was passed, and I got really sick [and wasn’t covered]. Once President Obama signed the new law into effect, I was able to stay on my parents’ insurance. When I went knocking on doors and trying to enlighten people about politics, that was [one of the things] I’d talk about. So it’s really just raising awareness and letting people know that you have to be out in the streets to bring about the changes you want to see.

I graduated from the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff in December 2010 and went on to work for President Obama’s reelection campaign in Chicago. That’s when I started developing a passion for [organizing] events. In the political world, we call that “advance.” Advance basically involves all the logistics and movement of a candidate who is running for office.

After President Obama won in 2012 I moved to DC and worked for the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco. I went on to work for Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2016, and that was devastating when she lost. It was a hard time for me personally. I lost my passion for politics. I gave it up, mainly because nobody would hire me for almost a year. [The loss] gave me a nervous breakdown and depression and I thought, ‘I can never put myself through this again.’

I ended up leaving DC and moved to Atlanta. I always wanted to own my own company, so after [Clinton’s loss] I just took it as a sign to start doing things my own way. That’s how Wilson Brand, my consulting firm, came about. I was hired to run the March For Our Lives tour with the Parkland [school shooting] survivors. We went around the country helping people understand how [this culture of] mass shootings affects the kids and [emphasizing] that we need to have better background checks to prevent kids from being killed. That experience helped lead me to an opportunity in Chicago, where I was doing a lot of community events for a PR firm, and then I moved back to Atlanta to manage Antonio Brown’s City Council race. That’s when I got my political spark back and I realized, ‘Maybe I’m still good at this,’ especially because we won.

In August 2019 I was hired to work on now-President Biden’s campaign. I was the National Advance Associate, a role which basically had me traveling the country setting up events not only for President Biden but also for First Lady Jill Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris.

What’s an average day like on the road?

It’s crazy. You might fly into a city, rent a car, go look at sites that could potentially be used for a rally. You’re doing walk-throughs with the Secret Service [for security purposes], drawing diagrams for the staging, working with the production team, building out the infrastructure so that when [the politician] comes to town it will be a successful rally. And then you go to the next city. So you’re living out of a suitcase. I did that for fifteen months [with the Biden campaign] and then went straight into the [Senator Raphael] Warnock campaign.

What are some of the qualities you’ve seen in these politicians that makes them successful?

For me it’s about how driven they are and how active they are in the community. I really believe in people who are down to earth and really want to make a difference. That’s evident in the people I’ve worked for who share the same views as me. I never want to see anybody struggle. I always want the next person to be able to have a seat at the table and have opportunities. Those opportunities aren’t always afforded to you as an African-American man, you know, we always have to strive harder, and I don’t want that to be the case. That’s why I was always [supportive] of President Biden from the beginning because [I’ve seen how] he was able to sympathize and empathize with people. He’s really [the type of] person who wants to see everybody succeed. That’s what I do every day: try to have a seat at the table and bring other people into the equation.

Do you think your presence can help open doors for more African-Americans and minorities in politics and help combat the perception that entertainment and sports are the only routes to success?

A lot of people [tell me] that they’re inspired by looking at my social media. On Election Day I had at least 20 messages from people telling me “Congratulations” and telling me, “If it wasn’t for you posting every day about Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, I wouldn’t have voted. This was my first time voting, because I saw someone who looked like me in the inner circle with these [politicians].” So people telling me that I’m the reason they went to vote for the first time, I think that really carries weight. During Reverend Warnock’s campaign, I was really putting my brand on it, posting pictures and videos from [the campaign trail]. So even for people who don’t know me personally, for them to see the level of access that I have and the situation that I’m in, it’s something I’m very grateful for and I hope it helps other people achieve [their goals].

The dual Senate runoffs in Georgia were a highly unusual situation. Because of a state law enacted in the 1960s, which many historians say was designed to undermine the power of black voters, elected officials in Georgia must obtain more than 50% of the vote. Reverend Raphael Warnock was one of twenty candidates vying for the seat opened by the passing of civil rights legend John Lewis, temporarily occupied by wealthy Republican donor Kelly Loeffler. Democrat Jon Ossoff was also challenging the Republican incumbent David Perdue. Because of the slim margin in the Senate, 50-48 in favor of the Republicans, these runoffs could determine the direction of the country for at least two years. Was that part of your motivation to get involved? Did this campaign ‘feel’ different, as in, did it have a sense of fate or destiny?

I knew what I had done for President Biden’s [campaign] and I knew [Warnock] needed the help, so I felt like I was in a unique position to help continue saving democracy. I felt indebted to Joe [Biden]. I know the inner workings of politics and I understand that governing and campaigning are two different things. When I got the call to help Reverend Warnock’s campaign, I knew I could add that flavor, not only with planning the events, but also making sure I’m elevating him [on all platforms]. When we’re going across the state we have him on livestreams, promoting him [on social media], and a lot of people told me, “On the event side, you really operated Reverend Warnock’s campaign [as if] it were a presidential campaign.” That’s basically what I set out to do. I felt indebted to [Biden] to continue answering the call of service and make sure we could rewrite [the direction of] history after, you know, the story of the last four years.

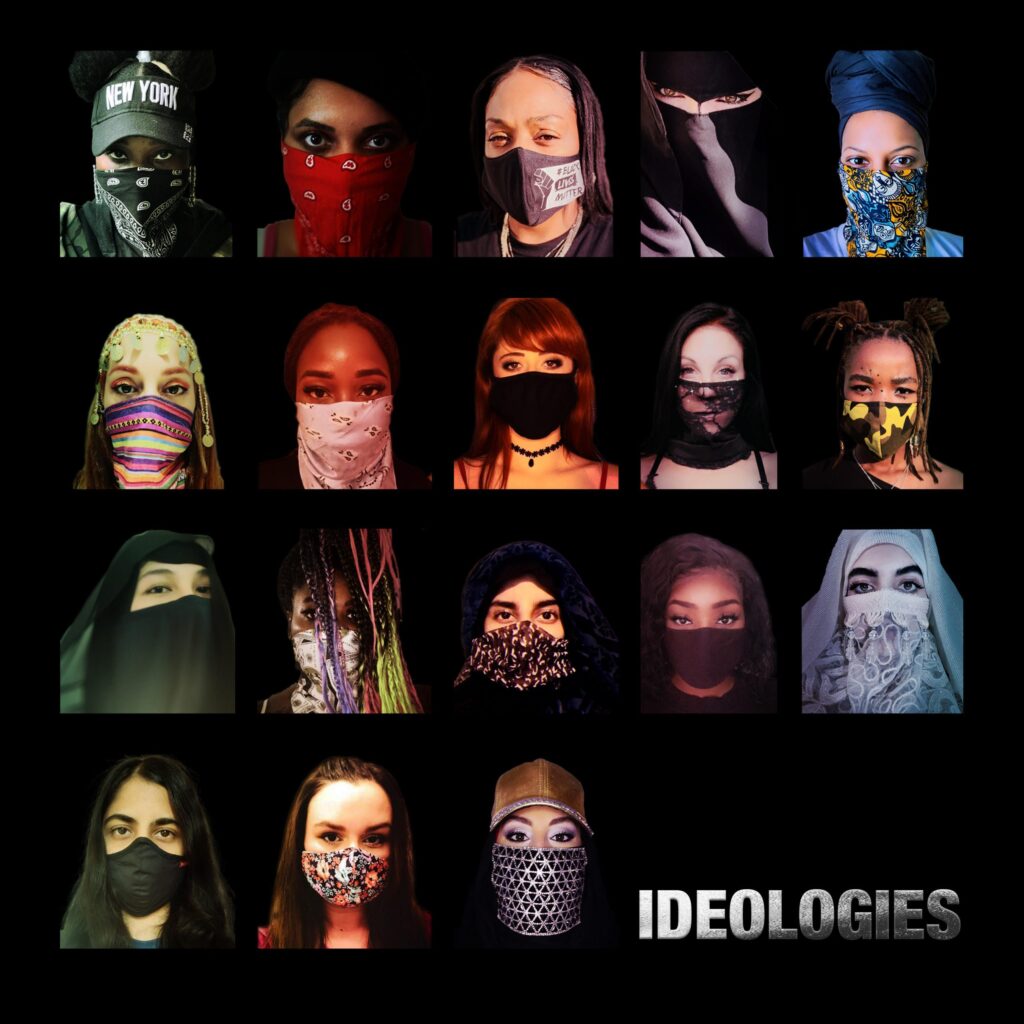

We saw during the campaign that a lot of hip hop artists got involved, like Jeezy and Jermaine Dupri and D-Nice. Is it difficult to walk that line of finding artists who are appealing but not too controversial in a way that might cause problems for the politicians? How did those situations come about?

I had a hand with Vice President Harris in [planning some of those performances at her events] and I was on the trip calls with her office, so, yeah, that definitely can be [an issue]. I remember talking to one of my colleagues and I was pushing for artists like Lil Baby, who is influential with the younger generation, to perform. But we do have to go through a vetting process when we’re bringing in artist. We have to look at their lyrics and the image that we’re putting out to the public. For example we did have Common perform. Common is an artist who caters to a wide audience and he’s also impactful with all the work he’s put in helping the communities. Jeezy has done that too. I actually was able to bring D-Nice to Georgia through a mutual friend. That really elevated the whole campaign experience, having D-Nice [DJ] in Savannah, Augusta, and Albany [on the campaign tour stops]. That’s one of my proudest moments because he [was so influential in 2020] keeping everybody rocking during the covid pandemic while we all had to quarantine at home. He’s also for the people. So you can bring the political side but in order to have far reaching [impact], we wanted to include musical artists in that equation.